Process After Product: An Electrate Model for Community-Based Learning

James Beasley

James Beasley is an associate professor at the University of North Florida, where he teaches courses in rhetorical history, theory, and pedagogy. His work has been published in College Composition and Communication, JGE: the Journal of General Education, Rhetoric Review, and Enculturation. His book, Rhetoric at the University of Chicago, is available through Peter Lang Publishing.

* * *

Introduction

In their history of service learning in English Studies, Laurie Grobman and Roberta Rosenberg write that community-based learning in English grew out of the debates in the 1990’s over whether literature should be taught in the composition course, “Service learning and research emerged in composition and rhetoric in the mid to late 1990’s. Some of these courses in rhetoric and composition included the reading and teaching of literature, though there was disagreement over literature’s role in composition classes by scholars in the field” (6). For Grobman and Rosenberg, the public turn in rhetoric and composition scholarship drove service learning in English, for “service learning was arguably an effective way to turn away from literature in composition and to focus on issues as literacy, academic discourse, and public writing” (6). It is the focus on community literacy that paved the way for literary courses to follow, as they write, “Composition and rhetoric’s continued focus on community literacy carves out an opening for the particular service learning work that can be accomplished through literary courses (6). For many, community literacy is the gateway to community service courses, whether their focus is composition or literary study. However, Grobman and Rosenberg also identify two problems that service-learning courses usually must overcome, the first being the “us-versus-them attitudes among privileged students who might see themselves as there to rescue the poor and minorities from their ‘plights.’ From this ‘savior’ perspective, students may ignore the community as a valuable partner and resource and knowledge making and problem solving and, as a consequence, may perpetuate oppression and exploitation” (4). The second problem is the kind of impact, if any at all, service learning has on actual community change. They write, “Further, while students may develop a greater awareness on social issues, their service may have minimal impact on the underlying factors that contribute to those issues,” or the “hit and quit” interaction (4). What is even worse, is that these problems may have been “baked in” to the beginnings of community-based learning in English, including Bruce Herzberg’s 1994 work with first year students as literacy tutors (6). Grobman and Rosenberg seem to understand the limitations of community literacy programs as the only model for community-based learning in English in their argument for a wider definition, and in order to achieve this broader understanding on the part of faculty and students alike, they identify several principles of good practice in service learning English classrooms:

Expose students to critical issues in service-learning scholarship, including the importance of public engagement, citizenship, and social justice.

Provide students with an awareness of current social problems and systematic injustice as well as the confidence to address the situations through community activism.

Integrate the literary in theoretical content of the course with service learning placements and activities by providing time in-class for students to make connections between their reading and civic engagement experiences.

Encourage students to ‘read’ both a literary and life experiences as part of their textual study and course work.

Require reflective writing and other critical thinking assignments that articulate both connections and dissonances between the reading of literature and service-learning experiences.

Allow for interdisciplinary research that helps students clarify and make sense of their experiences as literary readers and civic participants.

Assigned course projects or papers that benefit community partners may include the production of public writing, research, and oral presentations, performances, or oral histories (28-29).

Taken all together, faculty and students setting and achieving these goals would seem to negate the two most challenging problems of community literacy programs, the “savior” delusion and the inability to engage in a sustained way with complex social issues. As a new member of a community-based team of faculty teaching in my university’s honor’s college, I set out with these goals in mind, hopeful that my students and I would enjoy a transformational semester, both in our own learning, and in our communities.

Teaching the Process of Community-Based Learning

In the spring of 2017, I taught a version of first year of composition in the honors college.. I entitled this course Participatory Journalism, andin this course we read a number of readings from famous participatory journalists such as Charles Dickens, Ernest Hemingway, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, and Hunter Thompson. For their major assignment, students were required to choose any community partner from a list created by my university’s Center for Community-Based Learning. Once students chose their community partners, they were required to attend one of their partners’ events throughout the semester. After they attended that event, they had to write a report on what happened, using one ofTom Wolfe’s four techniques of the New Journalists: dialogue, scene-by-scene construction, status details, and third person point of view (46). The difficulties with this assignment were many, and the difficulties are not unique to our local area. For instance, Many community-based partners are understaffed, and students had difficulty getting their emails returned. When they did get emails returned, many of the events that the partners recommended had either already occurred or would happen after the semester was over. I was teaching the process to these students. I wanted them to identify a partner and the causes that they could identify with. I wanted them to initiate contact on their own, to learn initiative and entrepreneurship. I wanted students to then choose the specific event that would fit their interests and their causes, then write about that event using the techniques we had learned. I wanted them to write the “ideal” conclusion to the community-based learning course: the final reflection paper in which they identify all the ways in which their “lives have changed” as a result of attending the community partner event and writing about it. What ended up happening was that this linear process worked for only about one-fourth of the class. Most of the students finally ended up attending events on campus, or events sponsored by their church or in their neighborhood. The final reflections were positive, but not nearly as transformational for us as I had expected, and not at all helpful for any of the community partners I had hoped they would benefit.

Teaching the Product of Community-Based Learning

In the spring of 2018, I found myself teaching the same first-year composition course with a service-learning component. In order not to repeat the same mistakes, I began researching what prior experience these students might already have with community-based learning. I quickly began realizing that the linear process I had been trying to teach in the previous version of the class actually made community-based learning harder. Many of the students already had experiences with community partners that either were not on my university’s official list, or would never be defined as “community partners” at all. I had introduced a linear process into the students’ already-formed network of community alliances, interests, and even taboos. My process did not make it easier for these students to incorporate service learning in their coursework. In fact, my process interrupted them in the middle of their own service. In the course of my new research, however, I realized that these students had already been required to attend a community event and write a reflection on their experience from the previous semester. Because they already had a written product to show for their community engagement, that took care of many of the problems I had encountered the year before--students not being able to contact community partners or attend community events.

The focus of this class, therefore, also included instruction on Wolfe’s four techniques of New Journalism. But unlike the previous semester, students were able to work with their already written descriptions, finding new ways to tease out background characters and cultural understandings they had not previously considered.

In working with their revisions, I helped them see which of the four techniques they should use to revise. For example, a student who had visited a Middle Eastern restaurant had written that when he visited the restaurant “The owner said hello and the owner asked to know where they were from, and he apologized for the poor condition of the menus.” I worked with the student on using the technique of dialogue. So rather than saying that the owner “said,” we could actually hear the dialogue as it was spoken. Including dialogue allowed this student to experiment with dialects, and as he wrote in his own responses, he began to see some of his own cultural blind spots and his own cultural misunderstandings. Another student who attended a drag show had written about the flamboyant shirts of the performers. I worked with this student in utilizing the new journalistic technique of “status details,” that is, explain how a performer or an audience member’s shirt indicate the social status they held or wanted to have within that community.

At this point in the course, the students produced the final products that I had in mind for the end of the previous semester; however, they did so without the process that I had wanted to demonstrate in the previous semester. In other words, the first version of this class failed because the process thwarted our ability to produce products for the class or community. In this version, students completed the assignments for the class, but there was no process of “community-based learning.” It is at this point that the traditional reflection essay would now be assigned, as I had tried to do the previous year. But what if the failures of the first class were due to the focus of literacy itself in the English classroom? What if the problems of service learning, “the savior” complex and the “in and out” method demonstrate the limitations of literate practices of my own classroom? In order to get around these roadblocks, I began utilizing Gregory Ulmer’s work on electracy.

Electracy as Community-Engaged Learning

In Electronic Monuments, Ulmer writes that “the goal of electracy is easy to say in this context: to do for the community as a whole what literacy did for the individuals within the community” (xxvi). What most community-based learning models suggest is first an interaction between student and community and then a reflection by the student on that engagement. Ulmer’s “MEmorial” reverses this method, and this was useful in engaging students to understand new conceptions of community-based partners. The first step of the MEmorial for is the investigation of what he calls the “popcycle.” A popcycle is a series of images which correlate to the ways in which we encounter the world. The popcycle can have anywhere from four to six major areas: family, education, vocation, entertainment, church, community. Each student chooses an image which describes the particular epistemology of each of those popcycles. For example, a student whose family is described by “natural language” might choose an image of a diverse family all in conversation, whereas a student who would describe their family epistemology as “received knowledge” might choose an image of a family all seated at the dinner table with the father on one end and the mother at the other end [Figures 1 & 2]. After collecting these images, students narrow these images down to one of the four that they believe captures as many as possible [Figure 3].

Fig. 1. “Natural Language” (Image: Wavebreak Media Ltd.)

Fig 2. “Received Knowledge” (Image: Getty Images)

Fig 3. "Family porcelain plate" (Photo: Sawyer Johns)

Image 4. "Chora image" (Photo: Sawyer Johns)

Students then choose an image that they believe describes the message they are trying to promote in their revised community reflection [Figure 4]. The students now have two images: one image that captures the ways in which they view their own world and another image that captures the way the message they wanted to convey in their writing. Ulmer writes, “I juxtapose some documents from two domains (my life, the public problem), and the human sensorium does the rest. If a correspondence exists, the feeling occurs as an event” (147). Students begin to notice how the images they chose to describe how they view the world start to correspond to the images they chose to describe the message they wanted to explore in their community reflection papers. Ulmer describes this as the ME in MEmorial: “The method is to locate personal experiences or attitudes that form a pattern with the public issue, juxtaposed into an emblem that evokes for me and for others a moral group subject. What is the trajectory of the pain through me? I don’t explain Bradley’s abuse [or the accident you have identified], it explains me” (160). This is how the process comes after the product. Students began seeing that their reflections do not explain the community event. The fact they chose that community event and the message they want to convey after attending that event helps explain them. For many students, this was a powerful reversal. Students have become accustomed to writing reflection papers to describe their often non-transformational experiences. This was part of the class discussion, as well. After understanding why that location or event chose them, students learned that a community “partner” extends well beyond an understaffed office with limited budgets and limited resources. They questioned the assumption that a community partner meant only a partner to our “class,” and thought about how restaurants, clubs, grocery stores, car washes, etc., are “partners” with the community itself. They saw the Middle Eastern restaurant, the drag club, and even the local church whose views they detested, as community partners in new ways.

Augmented Reality and Community Service

Next in Ulmer’s process is to identify an object from one of the images that serves as the “peripheral,” an object from these images that triggers the “punctum,” the sting or prick that awakens our sense of social justice. Examples of such “peripherals” and “punctums” are Ghostbike Memorials, bicycles painted white and placed at locations where a cyclist has been struck by a motorist and killed. A white bicycle placed at the location where a cyclist was killed represents how that death is a sacrifice to petroculture.

The material placing of this trigger at a location is easily accomplished through augmented reality technology. For this particular project, students were taught the basics of augmented reality “triggers” and “overlays.” Students took pictures of signs at their community location, whether that be the logo for a restaurant or the logo for a community partner, or the logo for a community establishment. This image became the “trigger” image that when scanned revealed their popcycle images, their “punctum” images, and led to websites of community partners for information on how to join or support that community partner. For example, the student that wrote a dialogue with the Middle Eastern restaurant owner was therefore able to attach the website of a refugee organization to the sign of that particular restaurant. Any refugee attending that restaurant could simply use their phone to link to other refugee sources in the community [Figure 5].

Fig. 5. "Chora overlay" (Photo: Sawyer Johns)

In a poster session at the end of the semester, students were able to show participants how their images helped them understand why these community events and locations chose them. They could also show participants how augmented reality technology could help others contribute to their own projects. Ulmer writes, “The conventions . . . offered here as prototypes for a learning practice that is to Electracy what the argumentative essay is to literacy. The relationship building the memorial to the essay is not one of opposition but of supplement. The MEmorial takes up where the conventional paper leaves off” (xxiii). Their projects could be adapted and utilized by other students, faculty, and community-based learning partners and were not just final papers used primarily for grading or for community-based learning assessments [Figure 6]

Fig. 6. "Student overlay" (Photo: James Beasley)

Through these experiences, it is clear to me that community-based learning cannot be sustained through literacy, even though it is literacy and literate practices which continues to be the default drive of service-learning education. In this claim, I echo Thomas Miller and Melody Bowden’s examination of how literacy often prevents the opening of conversations on community-based learning. when they write the following: “The civic tradition needs to be critically reexamined to assess the limitations it imposed on public access, and the rhetorical strategies that were used to overcome them. A rhetorical stance on these issues, can provide us with a historical context for assessing, the technological and cultural changes that are transforming the public sphere, and the literacies of citizenship” (594). What is curious here is how Ulmer’s concept of electracy might assist more advanced students in doing this work, specifically the relationship between the “church” and “street” pop-cycles he writes about in Electronic Monuments. While Ulmer identifies several of the epistemologies of the family, entertainment, education, and career pop-cycles, he does not do so with the “church and street” pop-cyles in Electronic Monuments.

Fig. 7. "Church and Street Popcyles" (Photo: James Beasley)

Without Ulmer’s specific direction, these students examined what these might be, and we began compiling these lists. In the “Church” pop-cycle, the students identified that through the “church,” we come to know taboos and laws, worldviews and purpose, traditions and rituals, and sacrifice or offering. In the “Street” pop-cycle, students identified that through the “street,” we come to know community and boundaries, rights and responsibilities to others, safety and security, socio-economic class, and government and its administration [Figure 7].

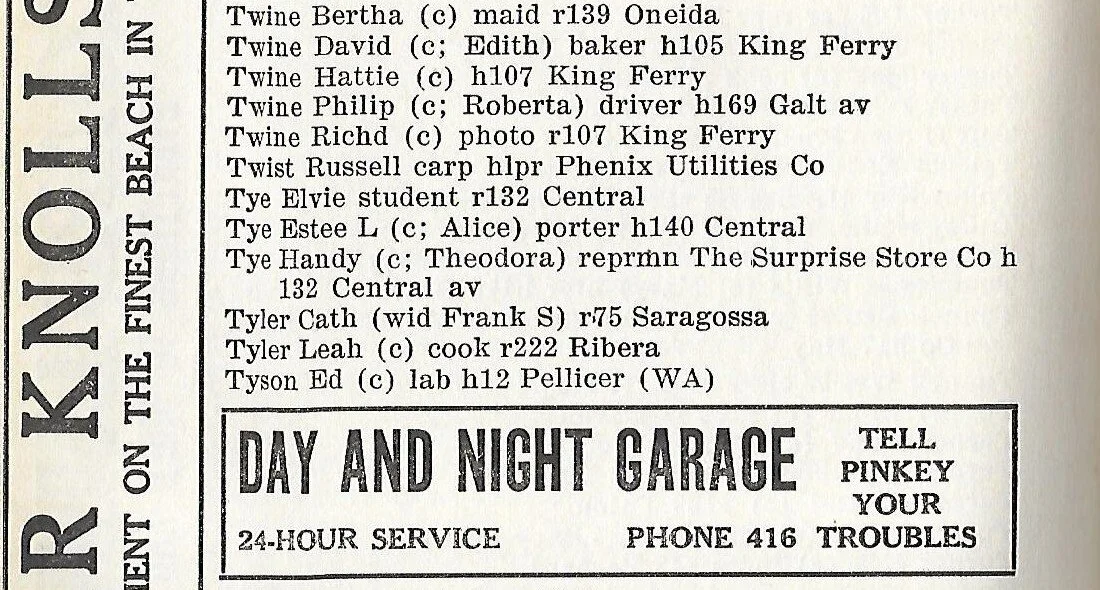

I was happy to have this help from these students, since I have recently been working with the St. Augustine Historical Society in St. Augustine, Florida, to curate online exhibits featuring the glass-plate photography of Richard Twine, a photographer who documented life in St. Augustine’s Lincolnville neighborhood in the 1930’s. Lincolnville was the center of African-American business in North Florida, and was the center of civil rights marches in the 1960’s. In a revision of my Rhetoric and the Digital Humanities course, students examined the city directories of St. Augustine in the 1930’s, and entered that metadata into the Society’s Omeka site. Rather than a “hit and quit” interaction, however, Graben, Ramsey-Tobienne, and Myers write that “a metadata program should be a model for question building, not for mapping their static locations.” So, for example, one of the biggest disappointments of the semester was when we learned that we would not have access to the church and school rosters from St. Cecilia’sCatholic School, even though I had seen and read through them in the archives. Graben, Ramsey-Tobienne, and Myerswrite about the opportunities of “Overcoming, or not being stymied by, evidentiary gaps in our archival knowledge, as we try to place persons and events” (240) While the students were initially frustrated that they would not be allowed to use church and school rosters to build more data on the subjects of Twine’s photos, the City Directories and their Dublin Core categories, provided a much richer way to understand these subjects. The City Directory identifies each subject’s occupation and, if known, their place of business. This data is recorded in the Dublin Core as Subject and Subject (added input). By having access to the city directories and not the church and school records, students got to know these subjects not by their church or school memberships, but by their work in their specific community. What began to take shape is a portrait of Lincolnville unfettered by religious homogeneity, but yet connected through a network of vocation and industry that honors the agency of the street, rather than the church [Figures 8 & 9].

Fig. 8. "After the Parade" (Photo: Richard E. Twine, courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

Fig. 9. "Father Knight" (Photo: Richard E. Twine, courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

This is where Ulmer’s “Street” pop-cycle became important. Students identified that through the “street,” we come to know community and boundaries, rights and responsibilities to others, safety and security, socio-economic class, and government and its administration. As students began working with the city directories, they began to see how the government of St. Augustine administrated these boundaries. Because the St. Augustine City government denoted African-American households with a “C” in the city directory, these student researchers encountered what Cara Finnegan calls the “fictive logic” of the archive. She writes, “Because the archive employs the fiction of denotation to tame the polysemy of connotation, the researcher also needs to learn and surrender to that fictive logic, in order to successfully engage the archival space. It is an unending dialectic” (119). While students began to understand the implicit racism of the records themselves, Ulmer’s “Street” popcycle helped them identify how the residents of Lincolnville might have understood their place within the matrix of a segregated southern society [Figure 10].

Fig. 10. "St. Augustine City Directory" (Photo: James Beasley)

Conclusions

This electrate model allows for competing values of community-based learning to co-exist. Grobman and Rosenberg’s tenants of community-based learning assume that all community partners are good actors—that student work must benefit the community partner in some way. But what if a community partner is a bad actor? Another of their goals is to get students to understand issues of social justice. But what if a community partner, so defined, is committed to intolerance? In this model, students understand social justice not because they were able to be paired with an organization dedicated to social justice, but because their writing criticizes a community partner dedicated to injustice, as in the case of the student who called attention to the intolerance of the local church in her neighborhood.

Utilizing electracy rather than literacy seems to discourage the “savior” mentality, and even more noticeably, the “hit and quit” interaction. Ulmer writes that “Public discussion remains fixed on the events, rarely reflecting on the frame of the events, never raising the structural questions that might help grasp the cause and function of private and public death” (35). By monitoring their own place within the matrix of community issues, how these issues have chosen them, students move beyond thinking of community events as temporal, but as fixed frames of community values.

So, through these experiences, I’m left curious as to whether the “archive” should be listed and added to Ulmer’s popcycle categories? Cara Finnegan writes that “I have come to embrace archival research, as a process of rhetorical negotiation, that parallels the demands of our other critical practices” (121). If this is true, should Ulmer’s list now feature home, entertainment, school, church, street, and archive? How can archival research decenter literacy practices? Can archival practice serve as a gateway to electracy? What do we learn about ourselves and others that we only learn from archival practice? And finally, how can the fictive logics of archives, help students see the fictive logics, that operate in their own communities or the communities of others, in the service of true community-based learning.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Works Cited

Finnegan, Cara. “What is This a Picture Of? Some Thoughts on Images and Archives.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs. vol 9, no. 1, 2006, pp. 116-123.

Graben, Tarez., Ramsey-Tobeienne, Alexis., and Myers, Whitney. “In, Through, and About the Archive: What Digitization (Dis) Allows,” in Rhetoric and the Digital Humanities, editd by Jim Ridolfo and William Hart-Davidson. 233-244. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Grobman, Laurie and Roberta Rosenberg, eds. Service Learning and Literary Studies in English. New York: Modern Language Association. 2015.

Miller, Thomas and Bowden, Melody. “A Rhetorical Stance on the Archives of Civic Action.” College English. vol 61, no. 5, 1999, pp. 591-598.

Ulmer, Greg. Electronic Monuments. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2005.

Wolfe, Tom. The New Journalism. London: Picador Publishing. 1973.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *