The List as an Invention Process

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

Barry Mauer is associate professor of English at the University of Central Florida, and recently served as director of the Texts and Technology doctoral program. His recent research is about citizen curating, which aims to bring ordinary people into the production of exhibits, both online and in public spaces, using archival materials available in museums, libraries, public history centers, and other institutions. Mauer publishes comics about delusion and denial, particularly as they affect politics. Mauer is also an accomplished songwriter and recording artist. He lives in Orlando with his wife and daughter, two dogs, and his cat.

John Venecek is a Humanities Librarian at the University of Central Florida. Where he serves as liaison to the departments of Art, English, Texts & Technology, and Writing & Rhetoric. His main areas of interest include open education resources, textbook affordability, and digital curation. Prior to becoming a librarian at UCF, John taught English for several years at the College of DuPage in Suburban Chicago and served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Ekaterinburg, Russia where he taught English and helped establish a foreign language library/resource center.

* * *

The List as an Invention Process

The list serves mundane purposes such as groceries and to-dos, but it also serves as an invention process. Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, first produced in 1975 and available in four editions, is an evolving list of over 100 instructions meant to help the creative person deal with common obstacles such as writer’s block. In our meditation on the creative possibilities for the list in humanist studies, the authors—John Venecek and Barry Mauer—took Brian Eno’s instructions both as directives and as subjects for inquiry, showing us a possible approach to rethinking the essay as a form and as a process.

Eno stated, “The function of the Oblique Strategies was, initially, to serve as a series of prompts which said, ‘Don't forget that you could adopt *this* attitude,’ or ‘Don't forget you could adopt *that* attitude.’"

These cards evolved from our separate observations on the principles underlying what we were doing. Sometimes they were recognized in retrospect (intellect catching up with intuition), sometimes they were identified as they were happening, sometimes they were formulated. They can be used as a pack (a set of possibilities being continuously reviewed in the mind) or by drawing a single card from the shuffled pack when a dilemma occurs in a working situation. In this case, the card is trusted even if its appropriateness is quite unclear. They are not final, as new ideas will present themselves, and others will become self-evident

Brian Eno/Peter Schmidt Oblique Strategies © 1975, 1978, and 1979

Working in alphabetical order, Mauer and Venecek selected one prompt per week from Eno’s list and responded to each with approximately 500 words, writing our sections separately. We took turns selecting prompts for each other so that one of us would always be surprised, which is a key aspect of Eno’s strategies and his composing process. At the end of the week, we shared our results and selected the next prompt. What we present here is the result of our summer-long experiment.

Abandon Normal Instruments – BarryAt stake is knowledge. Routine ‘instruments’ of scholarly research (questions, sources, methods) tend to produce routine knowledge. We are in extraordinary times . . . on the edge of apocalypse. Knowledge needs to expand. I propose an analogy between scholarly research methods and musical composition. A side of meat. A wooden box with a microphone inside it. A braying donkey. Jet engines. The tubax. These are some of the abnormal instruments Scott Walker used on his 2006 album The Drift. Walker composed with similarly strange “instruments”; slabs of sound, found lyrics, nightmare images, and far-fetched analogies (in “Jesse,” Walker links Elvis’s relationship to his stillborn twin to the Twin Towers on 9/11).

Fig.1: Kijak, Stephen. Stills from Scott Walker: 30 Century Man. YouTube (Kijak). 2006. Scott Walker, 1960s teen heartthrob, explaining to a percussionist how to punch a slab of bacon for his recording of “Clara,” 2006, a song about Mussolini’s mistress, who along with Mussolini was shot by partisans, then whose corpse was beaten and hung by the feet from a filling station canopy by a furious mob.

The “normal instruments” of writing pop songs Once you decide on the basic idea for your song, write out three or four lines that describe who’s involved, what’s happening, and how it feels. Try writing from the point of view of one of the people in the situation. It could be something that happened to you or, if you based your idea on a scene, imagine you’re one of the characters. Most hit Pop songs revolve around the singer or the singer and another person. So use “I” and “you.” Robin Frederick – “How to Write a Pop Song” The normal instruments of writing an essay are conventional steps; choose an area of knowledge (a topic), frame a research question, pose a hypothesis, gather materials, analyze and synthesize them, reach a conclusion, and compose an essay that keeps your audience and purpose at the forefront of the process. What happens when we deviate from this process? Can other “instruments” of research production and composition lead to knowledge worth sharing? For example, what if we abandon the normal instruments of essay composition and instead compose essays using the list? Brian Eno, in his list of over 100 instructions titled “Oblique Strategies” (first produced in 1975 and available in four editions) , shows us a possible approach to rethinking the essay as a form and as a process. |

Abandon Normal Instruments - JohnThe prompt evokes the following Brian Eno quote: “There are things that you can do when you're naive that you can't do when you're not naive anymore. For example, you'll never learn to draw like a child again so you have to accept that you can't do that and you say what you'll do is just draw as you are” (Eno 1975). Eno’s thoughts resonate because the theme of abandonment has recurred throughout my life, especially during my formative years when I would pursue areas of interest only to abandon them once expectations were raised and formality was introduced. For me, curiosity was about the process, not the product. As a result, I developed a transient nature. I was a dilettante – a constant dabbler exploring whatever piqued my interest without developing any real knowledge or expertise in any one area. As Eno suggests, there is something childlike about this kind of pursuit that cannot be replicated once the initial sense of wonder and innocence is lost. I began by developing a list of interrelated themes while listening to Eno’s most recent work, Reflection. In an interview with Pitchfork about Reflection, he states that the album is “less something you listen to and more something you use to color the air around you” (Sherburne). This thought gave rise to my initial entries: art, music, and color. Here are the other themes evoked during my first listen to Reflection:

Fig. 2: Eno, Brian. Reflection. Album cover image. Wikipedia. (Fair Use) 2016

|

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Bridges-Build-Burn - BarryI choose to take “bridges” literally and refer to the Tay Bridge, a lattice-grid design made of cast and wrought iron, which collapsed in 1879, killing either 74 or 75 people. The collapse led to a lengthy investigation and was followed by a major transformation in the design and construction of bridges. Its replacement, the Forth Bridge, used a cantilever design and was made of steel. It was voted Scotland's greatest man-made wonder in 2016 and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In this story, a disaster became a source of wisdom. Not all disasters lead to wisdom, though. Sometimes disaster leads to denial, delusion, doubling down, rationalization, and justification.

Fig. 3: Fallen girders near the Tay Bridge. National Library of Scotland. (CC BY 4.0) 1880. I choose to take “bridges” figuratively and refer to the way that the arts and disciplines create “bridges” as evolutionary steps within traditions (i.e. between blues and jazz). I am most excited by bridge-burning inventions in music and the arts in which artists like Louis Armstrong or the Beatles or Pablo Picasso learn traditional forms, then burn the bridges (many of them, at least) to these traditions and invent new vehicles to take them to new lands. “Weather Bird,” “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and “Portrait of Kahnweiler” are examples in which the burning of a bridge was key to the invention. What are the “disasters” of literacy? What are the structures that we need to burn so that something better can replace them? I can list a few:

To move past these disasters, I propose a massive investigation into their causes and consequences, as occurred after the collapse of the Tay Bridge. I also propose that we pour resources into a process of reimagining and reinventing literacy education, based in part on the invention methods practiced in the arts by such figures as Louis Armstrong, the Beatles, and Picasso, keeping in mind that their inventions were not purely works of genius by individuals, but also required the participation and collaboration of others. I have reversed two items in the prompt to suit my desires. Instead of Bridges-Build-Burn, I opted for Bridges-Burn-Build. The new bridge will replace the old collapsed bridge. |

Bridges-Build-Burn - JohnThere is something paradoxical about bridges. As literary critic Richard Gill notes, “They suggest both union and separation, distance and contact. Linking and joining what would otherwise remain separate, they also evoke the ‘transitional,’ the state of being in-between. Crossing a bridge graphically accentuates the passage from one stage to another, just as pausing on a bridge offers a vantage point for looking backward or forward, localizing the uneasiness of indecision or the finality of commitment” (Gill 147). I would add that you can simultaneously burn and build bridges.

Fig. 4: Venecek, John. The Palace Bridge in St. Petersburg. Personal Archive. July 1997. Responding to a question about creating music for an exhibit at the Great Gallery of Venaria can act as a bridge, Eno asks, “can we do something that will detain them in the gallery for a bit where, instead of just walking through and seeing it as a conduit between palace one and palace two, can they be slowed down so they start paying attention to that building?” In discussing that work, he evokes feelings like stillness, belonging, and freedom. “It was the sense of wanting to make something that felt like it had a place in the world,” he says, “rather than something that you just kind of stuck on for a little while to see how it works” (Anderson). The common theme among both these prompts is the sense that a lot happens in those liminal in-between states symbolized by the bridge. Playing off that idea, I reorganized the list I created in the first prompt by adding a few new terms and combining them into dualities that highlight those in-between spaces.

|

Cluster Analysis - BarryCluster analysis or clustering is the task of grouping a set of objects in such a way that objects in the same group (called a cluster) are more similar (in some sense) to each other than to those in other groups (clusters). – Wikipedia Clusters replace categories since they depend not on definitions but rather on affinities. These affinities form based on what Plato, the inventor of the definition, considered non-essential attributes. To Plato, a cow is still a cow whether standing or lying down, brown or white, long-haired or short haired, etc. The cluster can be heterogenous. One strategy – begin with a gathering of items that are as seemingly heterogenous as possible. I am currently working on a project that emerged from my reading of Ulmer’s Internet Invention, which is structured like a textbook with exercises and assignments. I completed all of these tasks (Ulmer told me he thinks I am the only person who has ever done them all). Thus, I have gathered and produced an enormous amount of raw material: 166 pages. The Ulmer strategy of clustering is to privilege the similarities among signifiers of those of signifieds. Thus, the following signifiers in my exercises became clustered:

Fig 5: Still from The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes. Dexter’s skull is the shell of a nut. The valuable stuff – the computer – is inside. See figure here. Patterns emerge – in this case, the pattern I identify is about bullying and impunity (it’s a long process, but somewhere in there is a news story about the secretary of the interior doing illegal lobbying work for cashew interests in California, hence the connection between nuts and bullying/impunity). Does this pattern emerge from an analysis (finding what’s there) or is there an imaginative leap in which I produce something? I tend to think it is a combination of both, but the word that seems most to describe this process is emergent. The words become attractants, both at the level of signifier and signifieds. As Ulmer notes in his gloss of Jakobson, “whatever resembles, assembles” (Ulmer, 2003). If I could illustrate this process, it would be through an animated GIF showing items moving from a field into clusters with networked pathways emerging to link other items. The list becomes dynamic! |

Cluster Analysis - JohnI first became interested in lists when I read Joe Brainard’s I Remember for a creative writing class. While his book is a common brainstorming activity, I took it as much more than that: An ethnography of the every day. Since then, I’ve read I Remember countless times while exploring like-minded authors such as Georges Perec, another documentarian of the ordinary, who wrote his version of I Remember that focused more on public events than personal memories. There is something uncanny about the structure of Brainard’s book. As Paul Auster notes in his introduction to The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, “whenever I open Joe Brainard's little masterwork again, I have the curious sensation that I am encountering it for the first time. Except for a few indelible passages, nearly all of the memories recorded in the pages of Remember have vanished from my own memory.” He also says, “The book remains new and strange and surprising—for, small as it is, / Remember is inexhaustible, one of those rare books that can never be used up” (Brainard). I would agree with Auster and add that I can’t read more than a few lines before being transported from Brainard’s world into my own. Without any conscious effort, I am flooded with memories or ideas for new lists. Brainard’s technique is both elusive and ephemeral, but it’s engaging in a way that blurs the line between author and audience. To get a sense of the type of marginalia that Brainard deals with, watch Matt Wolf’s short film adaptation of I Remember:

Fig. 6: Zev Weider, Avi, and David Chartier. Still from I Remember. YouTube. https://youtu.be/1ypRBhYsMDc. (Zev Weider) 1999. While the similarities between Brainard and Eno might not be immediately apparent, there are some similarities between their methods. Eno, for example, has compared his composing style to gardening, which, he says, “is essentially the idea that one is making a kind of music in the way that one might make a garden … carefully constructing seeds, or finding seeds, planting them and then letting them have their life.” Regarding the distinction between composer and listener he says, “I'm deliberately constructing systems that will put me in the same position as any other member of the audience. I want to be surprised by it as well. What this means, really, is a rethinking of one's position as a creator. You stop thinking of the situation as me, the controller, you the audience, and you start thinking of all of us as the audience, all of us as people enjoying the garden together. Gardener included” (British Council). In his analysis of Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports, John Lysaker states, “On this view, listeners are many, each an assemblage territorializing: playlists, collections, playback systems, maybe playback rooms, actions such as reading or tidying, even a misplaced gesture of adolescent seduction— “You have to hear this ambient record. . . .” The point is that these assemblages, or clusters, “remain cohesive sites of becoming and, like the weather, predictable across a range” (Lysaker). The notion of lists, or assemblages, as sites of becoming that is cultivated like a garden is similar to the reaction I have when reading Brainard and when composing lists. Brainard plants the seeds that blossom into lists that reveal new patterns, contours, and currents. |

Don't Be Frightened of Clichés - Barry

The cliché about clichés is that they are the opposite of invention. Clichés are old hat and invention is shiny and new. But what if we’re wrong about clichés? Writing students are told by their instructors to avoid clichés, but this instruction makes no sense to me. What if instead we teach people to use clichés? There’s a reason why clichés work. They reduce complex information to simple formulas. To that extent, essays are formulas. Narratives are formulas. Metaphors are formulas. One of the Coen Brothers’ most successful films, Fargo, was built on a series of stereotypes about Minnesotans drawn from Howard Mohr’s humor book, How to Talk Minnesotan, which is, as you might imagine, full of clichés. Information theory posits that pure information is pure noise. No information = pure redundancy: “Roses are red, violets are ___________.” I had a professor during my graduate studies at UF, Donald Ault, who drank roughly a six-pack of coke a day. One day I mentioned to him Andy Warhol’s Quote about Coke: You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it. Ault responded, “No two cokes are the same. No two sips of Coke are the same.” I understand where both Warhol and Ault are coming from. Warhol is thinking of the machinery of production eliminating difference. Ault is thinking of phenomenology and the Stoic rejection of category systems; nothing is even “itself.” Instead, as Deleuze states, there are “series.” No cliché is ever the same twice since it is in a new “place” each time. Even the same cliché twice in a row is not the same. See for yourself: “In the nick of time. In the nick of time.” What changed? Clichés oppose one another – The early bird catches the worm. YourDictionary advises: In the end, have some fun with clichés - they are easily recognized and understood - but use them sparingly. The first conclusion people jump to when they read too many clichés is that the writer is unoriginal. While that may not true, you don't want to set yourself up to be knocked down. This advice is itself a cliché. The heat death theory of culture – the new form is “hot.” Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Link Wray. They burn! Then the form cools into mass-marketed mediocrity: Pat Boone, Paul Anka. Then people get fed up with the cold stuff and they invent something hot again, like punk rock! But what is invention composed of but recycled materials, arranged, adapted, and mixed in new ways or in new contexts? Garbage in; genius out! Take a urinal, put it in a museum. A mass-produced item is now an emblem of modern art.

Fig. 7: Duchamp, Marcel. Fountain. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz. Wikipedia. (Public Domain) 1917. |

Don't Be Frightened of Clichés - John

One of my all-time favorite punk bands is the X-Ray Spex. In the pre-Internet days of my youth, my fascination was fueled by their obscurity. They were a somewhat mysterious band who released one studio album and a handful of rare singles that were nearly impossible to find in the U.S. As a young record collector, one of my white whales was their first single, Oh Bondage, which I eventually tracked down at Chicago’s Reckless Records for a tidy sum of $40. That would have been a quarter of my paycheck from whatever crappy job I was working. But that was okay. I had to have it. Although the A-side is considered a classic, I was equally fascinated with the strange B-side, I am a Cliché. At the time, I was all about rebelling against the clichés and the suburban stereotypes that dominated existence. It wasn’t hard because there were so many to choose from and so many of my bands like the X-Ray Spex confirmed my attitude: I am a cliché you've seen before In isolation, many of the lyrics now seem nonsensical: Yama yama yama yama yama yama - Poly Styrene

Fig. 8: Styrene, Poly. Cover art for “I am a Cliché.” Amazon. (Fair use) 1977. But you need to see the look and attitude of their flamboyant singer Poly Styrene for the full effect. I did my best to look as colorful and shocking as the X-Ray Spex and countless other bands right down to the torn clothing, painted jackets, and colored hair. But it wouldn’t be long before I realized that “being punk” is also a cliché. The same things that set me apart from my fellow suburbanites were all part of a uniform, a type of conformity. There’s no doubt about it: I was a cliché. There was an article that recently went viral entitled, “The Hipster Effect: Why Anti-Conformists Always End Up Looking the Same.” In it, the authors cite research conducted by Jonathan Touboul, a mathematician who studied the phenomenon through which members of counterculture movements undergo “a kind of phase transition in which members become synchronized with each other in opposing the mainstream. The hipster effect, he says, “is the inevitable outcome of the behavior of large numbers of people” (Emerging Technology). The deeper and somewhat paradoxical issue is how these movements begin organically, as authentic revolts against the clichés that dominate our daily lives before devolving into the very clichés they’re rebelling against. This dynamic is an inevitable cycle that has led me to wonder how and why the clichés we embrace shape our identities. Those of us in creative fields are trained to decry clichés as if they are the death of art even as we embrace them in our daily lives, almost to the point of necessity. Is the cliché, like the list, a form of invention? I will begin my analysis of this phenomenon by composing a list of the clichés I have embraced using the X-Ray Spex as my guide:

|

Emphasise Repetitions - BarryBe again, be again. (Pause.) All that old misery. (Pause.) Once wasn't enough for you. ― Samuel Beckett, Krapp's Last Tape

This is the three Rs, The three Rs: Repetition, Repetition, Repetition . . . ― The Fall, “Repetition”

The list has a basic form: descending verticality fused with the outline. It can be

The bulleted list is not hierarchical, but the numerical and alphabetical are. The descending verticality of the list paradoxically conflicts with the ascending numbers or letters that precede each item. In each numerical and alphabetical list, we go up as we go down. With this curious fact in mind, I emphasize the following list:

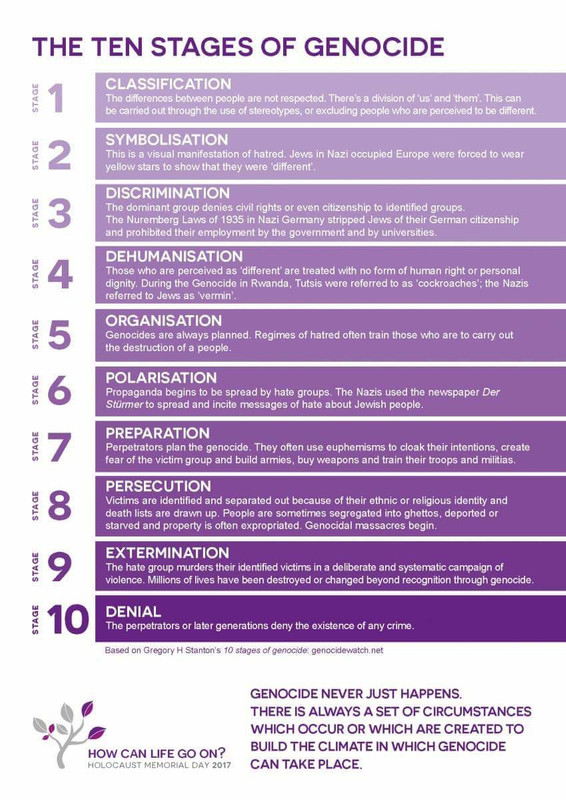

Fig. 9: Stanton, Gregory H. and the team at Genocide Watch. Democratic Underground. (Genocide Watch). 2016 In Samuel Beckett’s work, repetition coincides with decay. Between the first and second acts of Waiting for Godot, the characters repeat their actions and conversations, yet they also show a marked decline in their memory. In the etiology of addiction, repetition begets escalation. The links between addiction and trauma have been well documented. See “Childhood trauma among individuals with co-morbid substance use and post traumatic stress disorder.” Trauma repetition morphs into addiction. Bessel van der Kolk writes Trauma can be repeated on behavioral, emotional, physiologic, and neuroendocrinologic levels. Repetition on these different levels causes a large variety of individual and social suffering. . . previously traumatized people tend to return to familiar patterns, even if they cause pain. Addiction is trauma repetition plus escalation. People not only repeat previous cycles of abuse but tend to escalate them to include increasingly dangerous behaviors. With each iteration of the abuse-trauma cycle, the payoff or “high” per unit of stimulus diminishes while the real-world damage increases. Fascism, the precondition for genocide, is a collective form of trauma escalation and we are living it now. |

Emphasise Repetitions - JohnI remember little league practice and the endless repetition of fielding ground balls and shagging flies. We would complain to the coach, why do we have to do this? You need to learn the fundamentals, he’d say. We’d groan and go back to fielding ground balls and shagging flies. I remember learning to write in a notebook with dotted lines to guide you as you practiced making upper and lower case letters. I remember filling that entire notebook and getting marked down for every letter that strayed outside the lines. I remember countless hours spent reading aloud from our textbooks. We’d go up and down the rows for an entire class with each student taking turns reading a paragraph or two. I remember looking out the window until it was my turn and being scolded for daydreaming. I remember when my parents allowed me to start cutting the grass with our new riding mower. I was ten years old and that was the closest I would come to driving for six more years. I remember circling our yard, trying to align the tire tracks with each pass to create a uniform striped pattern. If I did it right, the last patch of grass would be the exact width as the mower… perfection! I remember hundreds of early mornings, standing on the same street corner in all kinds of weather waiting for the school bus to arrive. I remember hoping it wouldn’t show up just once, and my heart sinking each time I saw that first glimpse of yellow turning onto our block. *** A quick search on repetition reveals a complex array of ideas about the concept:

The list goes on… *** Brian Eno has said, “Repetition is a form of change” and “repetition doesn’t really exist.” While these two points may sound contradictory, his point is that “As far as your mind is concerned, nothing happens the same twice, even if in every technical sense, the thing is identical. Your perception is constantly shifting. It doesn’t stay in one place” (Eno 1985). This paradox is what makes his music equally elusive and alluring. It may seem like simple ambient music, but each listen reveals new layers and textures. No two listening experiences are the same. Eno’s thoughts echo my experiences creating lists. Not only is the process repetitious, I often repeat the same lists with little change to the content. But while the lists mostly stay the same, the experience is different each time. The repetition is the reaffirmation of my thoughts and convictions. For this experiment, I have returned to the interrelated themes of music, art, literacy, and identity. Within these themes, threads such as failure, risk, rejection, stillness, solitude, and boredom have emerged, all of which I plan to explore further in future writing projects. Each prompt provides a new way of looking at the repetition of recurring themes. In so doing, this process provides insight into how lists operate as an inventive activity and how the prompts have caused me to look at familiar topics in a new way.

Fig. 10: Weiss, Agathe. Rhizome. Flickr. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). 2015.

In the Bridges -build -burn portion of this essay, I mentioned that I’m interested in exploring the spaces between the themes these prompts -- along with Eno’s music -- have generated. Gilles Deleuze speaks to this point in Difference and Repetition when he asserts that in every form of repetition, something new is created. Just like no two leaves, snowflakes, or raindrops are the same, so too is there something unique and different about each moment and each repetition. This sense of difference is what drives creativity and invention, so every time I make that list of, say, the 25 most important people I’ve known, which I’ve done more than 25 times, the process is different even if the names rarely change. Once again, I am far more concerned with the process over the product. It’s all about possibilities. |

Faced with a Choice, Do Both (given by Dieter Rot)

But? AND! Two prompts, because “do both.” Dieter Rot (aka Roth), who gave Brian Eno the “do both” prompt, made artist’s books and produced other works using found materials including from rotting food. He collaborated with Daniel Spoerri on one of the most famous artist’s books ever made, An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, which Barry Mauer and Craig Saper drew upon for their article about lists. Rot also made a “book” in 1961 titled Literaturwurst (Literature Sausage). The first “copy” was made from an issue of the Daily Mirror together with food and spices from actual sausage recipes, which Rot stuffed in a sausage skin and sent to Spoerri. From Wikipedia: Literaturwurst (Literature Sausage) is an Artist's book, made by the Swiss-German artist Dieter Roth between 1961 and 1974. Each book was made using traditional sausage recipes, but replacing the sausage meat with a book or magazine. The cover of the edition was then pasted onto the skin of the sausage and signed and dated.

Fig. 11: Rot, Dieter. “Literature Sausage.” Dieter Rot Foundation. Wikivisually. (Hauser & Wirth and Staatsgalerie Stuttgart). 1961. Gilles Deleuze, in The Logic of Sense, explained that “sense” is the boundary between the material world (nonsense) and signification. Sense keeps words from collapsing back into things. Thus, we can apply the term “book” to Literaturwurst, but in what way does this designation make “sense”? The image above shows a picture of a man (who is on a sausage) pointing, but not at something. Rather, we read him as “making a point.” At what “point,” John Brady asks, does a hand become a hand that points? At what point does a book (or newspaper) become a sausage? At what point does a sausage become a book or become art? And what is the point? Fill every “beat” with something. The skin of a sausage / the skin of a drum to beat: both made from animals. The beat is a key term in drama theory. As Bill Bruehl writes, “A new beat begins with a new action or a new mood, and we can identify new beats by that change of mood or action and often by the coming or going of a character. The flow of action is not limited to one action per beat.” The sense – filling every beat – taking a piece out of an animal. |

Faced with a Choice, Do Both (given by Dieter Rot)

Lists are like jazz. They are both deliberate and improvised. They are as rooted in tradition as they are playful and spontaneous. As acts of invention, they are best when impulsive. Each has a sense of rhythm and momentum but they’re full of bent tones and blue notes. And they do what these prompts suggest: When faced with a choice, they provide the space to “do both” and to “fill every beat with something.” In an interview about improvising within the rules, Brian Eno recalls his collaborations with Peter Schmidt and about how they kept separate lists of rules for what they thought made a successful composition. They drew from their lists during their collaboration, but they never shared their rules. In this way, the rules were the hidden structure within their work. One of the rules Eno applied then and still uses to this day is to "Honor thy error as a hidden intention." The concept of rules might seem counterintuitive and constraining, but Eno finds that for improvisations, if each player takes one of those cards and keep them to themselves, don't tell anyone what rule they're operating under, that can produce some really interesting results. People tend to play in their comfort zone, so the best things are achieved in a state of surprise, actually … I wanted to set up a way to get people to shut up sometimes, because a big problem with improvisation is that everyone plays all the time unless told not to Eno (2010)

Eno also discusses a more recent collaboration with Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams for The Lovely Bones soundtrack, a collaboration so productive that they had enough remaining music for a second album. On a similar note, in “Sew the Bear: A Meditation on the Place of the List in Academic Life,” Barry Mauer states that, The muse did not learn to write by starting with the lyric or the epic. She first wrote lists. Bob paid his taxes with three oxen and two jugs of oil. He still owes a cow and three bushels of wheat. Literature came later, unless you consider the list to be a form of literature, which I do. In response, Craig Saper writes With every detailed list comes the inevitable stray-mark, what Roland Barthes called the asemic -- not yet signifying what's next in the literate list -- but signaling how even the most careful accounting has a remainder that will never make it on to the list. I would make a slightly different point; that lists exist in the realm of the remainder. As discussed in the Cluster Analysis portion of this essay, my list-making revolves around documenting the detritus of the every day; the fleeting ephemera that goes unnoticed or is easily forgotten. These are the marginalia, or the remainders of our lives. The list-making process can be contradictory, constructive, and destructive, but it always provides the freedom needed for self-expression with just enough structure to reveal “the error of the hidden intention” and, as this prompt suggests, “Fill every beat with something.” |

Works Cited

Anderson, Laurie. “Brian Eno.” Interview Magazine. 21 Jan. 2013. https://www.interviewmagazine.com/music/brian-eno Accessed August 28, 2019.

Brady, John. “Deleuze on Sense, Series, Structures, Signifiers and Snarks (Part B).” Epoché Magazine. June 17, 2017. https://epochemagazine.org/deleuze-on-sense-series-structures-signifiers-and-snarks-part-b-f4af57d5e554 Accessed August 28, 2019.

Brainard, Joe, et al. The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard. Library of America, 2012.

British Council. “Brian Eno: 77 Million Paintings in Sarajevo.” British Council Music. 2016. http://music.britishcouncil.org/projects/brian-eno-77-million-paintings-in-sarajevo Accessed August 28 2019.

Bruehl, Bill. The Technique of Inner Action: The Soul of a Performer's Work. Pearson Education, 1996

Deleuze, Gilles. The Logic of Sense. Trans. Mark Lester with Charles Stivale, ed. Constantin V. Boundas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990).

Duchamp, Marcel (1887–1968) Fountain. Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz. Captions read: "Fountain by R. Mutt, Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS." The Blind Man No. 2, page 4. Editors: Henri-Pierre Roche, Beatrice Wood, and Marcel Duchamp. New York, May 1917.

Emerging Technology from the arXiv. “The Hipster Effect: Why Anti-Conformists Always End Up Looking the Same.” MIT Technology Review. 28 Feb. 2019. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/613034/the-hipster-effect-why-anti-conformists-always-end-up-looking-the-same/ Accessed August 28, 2019.

Eno, Brian. Personal Interview. NPR. 29 Oct. 2010. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=130918991 Accessed August 28, 2019.

Eno, Brian. Personal Interview. Keyboard Wizards. Winter 1985. http://www.moredarkthanshark.org/eno_int_key-wiz-win85.html Accessed August 28, 2019.

Eno, Brian. Personal Interview. Hyperreal Music Archive. 1975. http://music.hyperreal.org/artists/brian_eno/interviews/unk-75a.html Accessed August 28 2019.

Eno, Brian, Peter Schmidt. Oblique Strategies © 1975, 1978, and 1979. http://www.rtqe.net/ObliqueStrategies/ Accessed August 28, 2019.

“Examples of Clichés.” Your Dictionary. https://examples.yourdictionary.com/examples-of-cliches.html Accessed August 28 2019.

“Fallen Girders Near the Tay Bridge.” Great Britain. Board of Trade. 1879-1880.

Farrugia, Philippa L et al. “Childhood Trauma among Individuals with Co-Morbid Substance Use and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.” Mental Health and Substance Use: Dual Diagnosis vol. 4,4 (2011): 314-326. doi:10.1080/17523281.2011.598462

Frederick, Robin. “How to Write a Pop Song.” https://mysongcoach.com/how-to-write-a-pop-song/ Accessed August 28, 2019.

Gill, Richard. “The Bridges of St. Petersburg: A Motif in Crime and Punishment.” Dostoevsky Studies: Journal of the International Dostoevsky Society, vol. 3, 1982, pp. 145–155. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=1982059636&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Kijak, Stephen. Stills from Scott Walker: 30 Century Man. 2006. https://youtu.be/JEYWGQMqC74. Accessed August 28, 2019.

“Literature Sausage” - Dirk Dobke/Dieter Roth Foundation: Dieter Roth - Books and Editions, distributed by Thames and Hudson, 2004. The right to reproduce the work for dissemination and discussion has been sought, and gained, from Dirk Dobke, executor of Roth's estate, with the request that the source is cited and © Dieter Roth estate is included.

Lysaker, John. “Turning Listening Inside Out: Brian Eno's Ambient 1: Music for Airports.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 31, no. 1, 2017, pp. 155–176. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jspecphil.31.1.0155. Accessed August 28, 2019.

Mauer, Barry, and Craig J. Saper. “Sew the Bear: A Meditation on the Place of the List in Academic Life.” Hyperrhiz, no. 19, Winter 2019, pp. 1–12. EBSCOhost, doi:10.20415/hyp/019.g03.

Sherburne, Philip. “A Conversation with Brian Eno About Ambient Music.” Pitchfork. 16 Feb. 2017. https://pitchfork.com/features/interview/10023-a-conversation-with-brian-eno-about-ambient-music/ Accessed August 28, 2019.

Slichter, Jacob. “The Audience Learns Part 2 — Repetition.” Portable Philosophy. 26 Feb. 2015. http://www.portablephilosophy.com/all/2015/2/15/the-audience-learns-part-2-repetition Accessed August 28, 2019.

Styrene, Poly. “I Am A Cliché.” Genius Lyrics. https://genius.com/X-ray-spex-i-am-a-cliche-lyrics Accessed Aug 28, 2019.

“The Ten Stages of Genocide.” 2017. https://www.gmpmuseum.co.uk/holocaust-memorial-day/ Accessed August 28, 2019.

van der Kolk, Bessel. “The Compulsion to Repeat the Trauma. Re-enactment, Revictimization, and Masochism.” Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1989 Jun;12(2):389-411. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2664732 Accessed August 28, 2019.

Venecek, John. Personal Photo of The Palace Bridge in St. Petersburg. Summer 1997.

Warhol, Andy. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1977.

Weiss, Agathe. “Rhizome.” Flickr. 10 Sept. 2015. https://flic.kr/p/xuKbqR Accessed August 28, 2019.

Wolf, Matt. “I Remember.” 30 June 2012. https://youtu.be/1ypRBhYsMDc Accessed August 28, 2019.